Email us to revise your entry or request it to be deleted.

AIDS Trilogy

United States of America

B/W

English/English

Want to add a content warning? Email us!

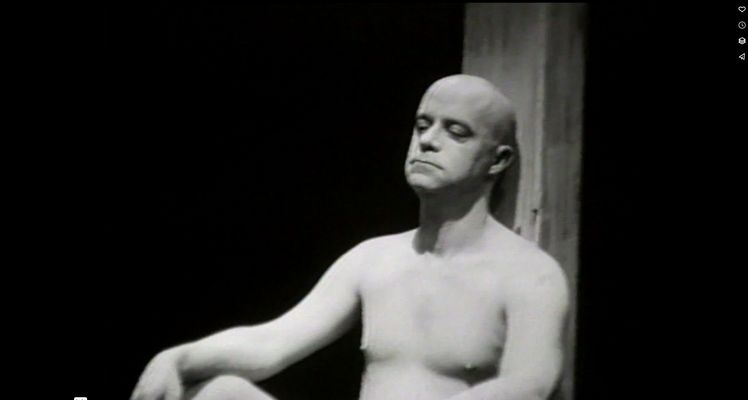

In the 1990’s, as losses continued to mount in the AIDS pandemic, I began creating elegiac films to mourn, rage, celebrate, and feel less helpless. Here are three works from that period. UNFORGIVEN FIRE (1993) Late night phone calls still frighten me. Years ago, my neighbor, Charlie, would call in the middle of the night, screaming through his dementia for help—begging us to get him out of the hospital, away from his real and imagined demons. I wouldn’t answer the phone; I could only listen to his voice coming through the answering machine. Silent and paralyzed with fear, I thought there was nothing I could do. I never did visit him in that hospital. I was too ashamed, and he never came home again. I remember holding Peter, trying to warm his shivering body—hoping that somehow I could heal him, even for a short while so that he would sleep. Both of us were drenched in his night sweats. He kept apologizing as he cried. I wept, too, but my tears were filled with rage. Earlier that day, we had spent hours waiting in lines, filling out forms that enabled him to get medications. He had no health insurance, and each stop demanded that he be present to sign the proper forms. So he sat exhausted and consumed by his fevers while I held his place in line. Months later, I dreamt of him and called, only to speak to his daddy. Peter had died that morning in Michael’s arms, as his mama urged him to go on. I called my friend, Lee, at home to see how he was feeling. I had just returned from an extended business trip and wanted to reestablish contact. His sister answered the phone, thanked me for calling, and asked if I wanted to share something with those gathered in the apartment for his memorial service. Selfishly, I felt cheated that I wouldn’t have any private closure with him. Weeks afterward, I called his disconnected number, hoping we could talk one last time. Months later, I called his phone number again, explaining to the newly connected household how special my friend Lee had been. When the call came ending Kevin’s deathwatch, I was relieved. Three weeks prior, the doctors had stopped his feeding, upped the morphine, and said he would go in 48 hours. But they didn’t know the Kevin I did. We were lovers a decade ago: We trained together, made love together, and dreamt our dreams together. Upon hearing the news, I thought at least I wouldn’t have to call the hospital anymore. In his last month, with the morphine obliterating all feeling, I would call and be continually told his condition was “satisfactory, SATISFACTORY, (satisfactory), satisfactory.” Most recently, I cried with my friend, Margie, over the death of her brother, Christopher. Margie told me of crawling into Christopher’s deathbed to hold him. As his spirit began to leave, instead of releasing, his body contracted (as only a dancer could) and tightly embraced her. She held on, knowing that he was going, leaving her with the unfinished legacies of all those prematurely lost. He had chosen to die peacefully with great clarity, letting Margie know that his work was now done, but hers and ours only begun. They’re all gone now—96 of my angels. For all too many of them, I didn’t get to say goodbye. I wanted to. I still need to somehow resolve the forlorn reality of their death. The impact of the grief and the mourning of each new loss remains as intense as the first. Oftentimes, late at night, it is hard for me to breathe, as I cry for all the devastation among us. Heroes, all of them, so needlessly lost. I am truly blessed to have been touched by them all—to have been loved by angels. For all of us that have gone before and for those that remain, may there be passionate, unforgiven fire.

-

Assistant Director/Unit Director/Co-Director

Email us to revise your entry or request it to be deleted.